Page: 1 | 2 |

Pregnancy

Posted September 30th, 2010 | PermalinkChoose an English translation to read this passage in its context:

World English Bible | English Standard Version| New International Version

This passage is from the book of Hosea, written in the eight century BC. The Assyrian empire was relatively weak for the first half of this century, until Tilgath-Pileser III came into power and lead a series of conquests. Assyria conquered the northern kingdom of Israel in the 720's BC, and took captive its citizens.

Hosea, an Israelite and a prophet of the god Yahweh, predicted destruction for Israel and its capital city Samaria, as can be seen in the passage I've quoted in the picture. He seems unsure, though, on who will carry out the destruction and what will happen to the Israelites. 8:13 says they will return to Egypt. 9:6 seems to say that Egypt will conquer them: "Egypt will gather them up. Memphis will bury them." 9:3 says they will go to Egypt and to Assyria. But 11:5 says that they won't return to Egypt, and that Assyria will be their king. However, 14:3 says that Assyria can't save the Israelites from the coming destruction, which is an odd thing to say if Assyria was to be the one causing the destruction.

Hosea believed that the people of Israel and Judah had made a covenant with Yahweh, and part of the agreement was that they were to worship no other gods but him. Hosea was in the minority in thinking this, however, as most Israelites worshiped multiple gods in addition to Yahweh. For example, Israel had calf idols which they worshiped (Hosea 8:4-6, 10:5, 1 Kings 12:25-33). King Ahab of Israel had built a temple to the god Baal in Samaria (1 Kings 16:32). Hosea writes that destruction is coming as a punishment because of this unfaithfulness to the covenant with Yahweh. In chapter 1, Yahweh tells Hosea to marry a prostitute named Gomer. Marriage to an unfaithful wife is then used throughout the book as a metaphor for Yahweh's covenant with Israel.

Since prophets such as Hosea ended up being correct– destruction did in fact come to Israel– their view about exclusivity in Yahweh worship apparently became influential. In the latter half of the 7th century BC, after the fall of Israel and with the threat of being conquered by Babylon looming over the nation of Judah (the southern Hebrew kingdom which hadn't been conquered by the Assyrians), Josiah king of Judah instituted religious reforms which tried to remove the worship of gods other than Yahweh, including the execution of all the priests of the other gods. Thus, the view that only Yahweh should be worshiped started to become the mainstream view among the Hebrew people, and the histories which they later wrote, such as First and Second Kings, spoke in condemning terms whenever worship of the other gods is mentioned.

| Questions? Comments? Email me at fred@bibletastic.com |

Women

Posted August 30th, 2010 | PermalinkChoose an English translation to read this passage in its context:

World English Bible | English Standard Version| New International Version

Forgeries and fabrications were extremely common among ancient literary works. For example, The Acts of Paul, which contained a third letter to the Corinthians (purportedly written by Paul), was confessed to be a forgery by its author. Tertullian writes concerning it:

...in Asia, the presbyter who composed that writing, as if he were augmenting Paul's fame from his own store, after being convicted, and confessing that he had done it from love of Paul, was removed from his office.Another example would be when the Roman physician Galen

The passage which I've quoted in the picture represents one example of the differences between the Pastoral Epistles (First Timothy, Second Timothy, and Titus) and the genuine letters of Paul by which it is known that the Pastoral Epistles are not written by Paul, but are forgeries written in his name.

In the genuine Pauline letters, it can be seen that Paul was in favor of women playing an active role in the Jesus movement, including speaking and teaching in the assemblies. For example, in Romans 16, Paul writes greetings to many women whom he considers fellow workers in the gospel, including Junia– apparently an apostle– whom he praises as "distinguished among the apostles". He also sends his greetings to Phoebe, the deacon of the church in Cenchreae. In other letters he speaks of men and women being equal: Galatians 3:28, 1 Corinthians 7:3-5.

In contrast, in the Pastoral Epistles, we can see the start of the marginalization of women in Christianity. The author is against women being teachers or leaders, and wants them to be completely silent and submissive. The reasoning given is that Adam was the one made first, then Eve. Plus, Eve was the one who was deceived– the implication possibly being that women are more easily deceived than men, and if they were allowed to be teachers, they could pass deceptions to the men as Eve did. But for all their faults (according to the author) there's still hope for women– it says they can be saved through childbirth!

1st Corinthians– a genuine letter of Paul– also has a passage that says that women should be silent: 14:34-35. However, it can be seen that this part was added by a later scribe by, among other things, the fact that among the available manuscripts, those of the Western text-type place those two verses after verse 40, instead of after verse 33, as in the manuscripts of the Alexandrian text-type. The passage likely originated as a margin note added by a scribe, which later got incorporated into the text– some scribe inserting it after verse 33 while making a copy, and a different scribe adding it after verse 40.

Another indication of the different historical setting in which the Pastorals were written are the references to Gnostic Christianity in 1 Timothy 1:4 and 6:20. Gnosticism was a later development in Christianity– it did not exist in Paul's time.

Although the significance of vocabulary differences has been disputed, it should also be noted that the large difference in vocabulary between the Pastorals and other Pauline letters is another reason for thinking that the Pastorals are forgeries. P. N. Harrison's 1921 book The Problem of the Pastoral Epistles shows that of the 848 words contained in the Pastoral Epistles, 306 do not occur in any of the other 10 Pauline letters. Plus, the vocabulary of the Pastorals matches much more closely to that of the later second-century Christian writings than the other 10 letters do (page 26).

The writings of the early Christians also stand as evidence against Pauline authorship of the Pastorals. There is no quote from the Pastoral Epistles before Irenaeus in 170AD. Also, the earliest known canon of Christian scriptures consisted of a modified Gospel of Luke and Paul's letters– but did not include the Pastoral Epistles (Against Marcion, book 5 ch. 21). This canon was compiled by Marcion, whom I've mentioned in a previous post.

| Questions? Comments? Email me at fred@bibletastic.com |

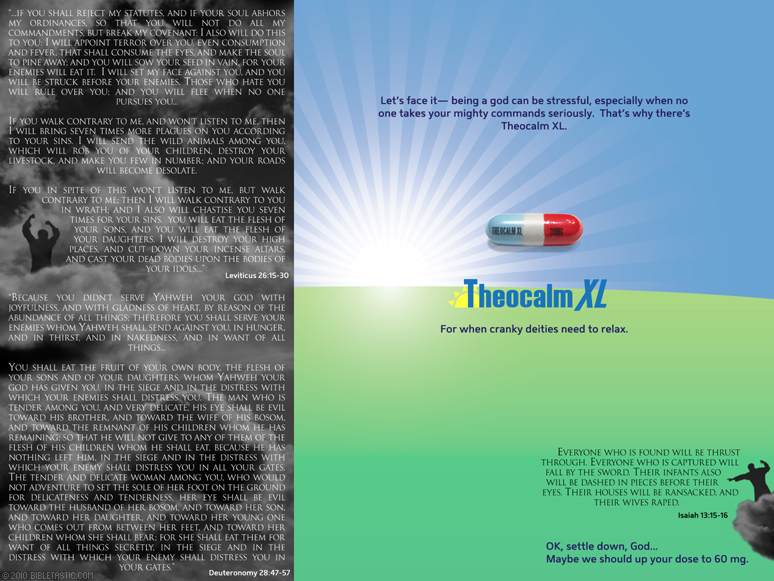

Theocalm XL

Posted February 15th, 2010 | PermalinkIn the books of the Old Testament, the agreement that the god Yahweh makes with the Israelites is in the form of the type of suzerain-vassal covenant typical in the ancient Near East. These covenants would normally specify the terms of an agreement between a king and a people who would have to pay tribute to him. A section of these covenants would be devoted to the curses that would happen if the vassal breaks the agreement. Leviticus and Deuteronomy each have their own version of this part of the covenant with Yahweh, from which I've quoted in the picture.

One example of a similar covenant outside of the Bible is a treaty from 1280 BC between the Hittite king Muwatalli II and Alaksandu, king of Wilusa. See Dennis J. McCarthy's book, Treaty and Covenant: A Study in Form in the Ancient Oriental Documents and in the Old Testament for a comparison of each section of this covenant with Deuteronomy. The main difference is that, normally, covenants would have a section where gods would be listed as witness to the covenant, but since Yahweh himself was a god, there was apparently no need for this part of the Yahweh-Israelite covenant. Another example are the treaties of the Assyrian king Esarhaddon. Some of the curses in these are the same as those in Leviticus 26 and Deuteronomy 28.

So, the covenant that Yahweh makes with Moses and the Israelites essentially states that Yahweh would be the Israelites' god, would protect them, make them prosperous, and help them defeat their enemies. The Israelites' part of the agreement was that they would have to worship no other god but Yahweh and obey all his commands. The punishments for the Israelites breaking the covenant included Yahweh making them eat their own children.

However, the view that only Yahweh should be worshiped was apparently either a minority view or a later literary invention. This can be clearly seen by reading Judges, 1st and 2nd Samuel, 1st and 2nd Kings, and 1st and 2nd Chronicles. In these histories, most Israelites are constantly worshiping many gods in addition to Yahweh, such as Baal and Asherah. Whenever a disaster happens to the people, such as being conquered by the Philistines, the compilers of these books blame it on the Israelites' worship of those other gods. Even as late as the fifth century BC, Jews were still polytheistic, as can be seen in the Elephantine papyri, writings written by a Jewish colony in Egypt. For example, one papyrus contains an oath sworn by a Jew to Anath (apparently the wife of Yahweh) and to another god.

The other passage I put in the above picture is from a chapter of Isaiah describing the “Day of Yahweh”, when Yahweh would gather an army and kill all the sinners in Babylon. This is part of the first section of Isaiah, which was written around the same time as the core sections of Deuteronomy— while Judah was a vassal state to Assyria, before they were conquered by Babylon.

For the quotes in this picture, I used the World English Bible translation, instead of translating it myself this time from the Septuagint.

Choose an English translation to read these passages in their contexts:

Leviticus 26:

World English Bible | English Standard Version| New International Version

Deuteronomy 28:

World English Bible | English Standard Version| New International Version

Isaiah 13:

World English Bible | English Standard Version| New International Version

| Questions? Comments? Email me at fred@bibletastic.com |

Zombie Invasion!

Posted September 7th, 2009 | PermalinkThis, of course, is from the story of the resurrection of the dead towards the end of the Gospel of Matthew.

Among the early Christians, the gospels were not static, unchanging documents, but rather were freely changed and added to. For example, the earliest available copies of the Gospel of Mark have four different endings. Another example would be the fact that the "cast the first stone" story in the Gospel of John does not appear in the ancient manuscripts until the fifth century Codex Bezae (F. 133b through F. 134b)

The gospel of Matthew is a copy of the Gospel of Mark with some rewording and stories added to it. Almost every verse of Mark is included in Matthew, and almost always in the same order. Much of it is reworded, and much of it is taken word-for-word from Mark. By comparing the two books, and seeing what changes the author of Matthew made, one can see what his intentions were in compiling this gospel. One of his main intentions seems to be to convey to his audience that Jesus was the Jewish messiah prophesied about in the Jewish scriptures.

This story in the quoted passage about holy people raising from the dead at the time of Jesus’s death is one such example of the author inserting a story with that intent. Jewish writings that predicted a resurrection of righteous people include Isaiah 26:19, Daniel 12, 2 Maccabees 7:9, 7:14, 7:23, 12:43-45, and 1 Enoch 51.

If one compares Matthew and Mark in their original Greek, it becomes easy to see exactly what parts in Matthew came from Mark, and what parts were added. Click here to see the context of this story compared to the corresponding section in Mark. I’ve highlighted in red where the words are the same in the corresponding verses.

Choose an English translation to read this passage in its context:

English Standard Version | King James Version| New International VersionCompare with its parallel passage in Mark:

English Standard Version | King James Version | New International Version| Questions? Comments? Email me at fred@bibletastic.com |

Older Posts: 1 | 2 |

Copyright © 2008 - 2010 Bibletastic.com